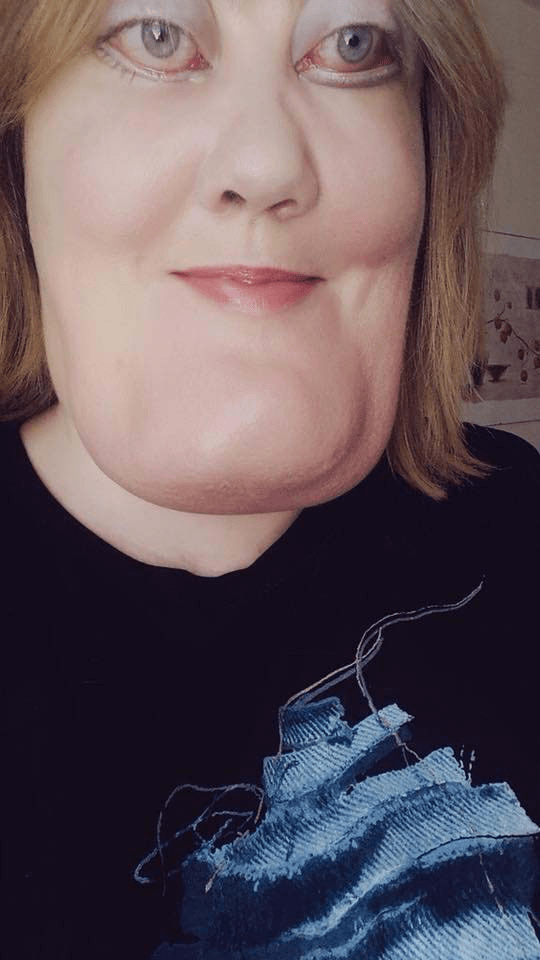

Victoria Wright was born with cherubism, a relatively rare genetic disorder. The lower region of her face had an abnormal bony overgrowth, and the first indicators appeared when she was four years old. Doctors didn’t know what was causing the problem at first.

Wright’s face, according to physicians, is as hefty as a bowling ball. She experienced bullying at school and even on the bus as she grew older. Regardless, Victoria was resolved to live her life to the fullest, refusing to let the bullies triumph. She is now a fantastic role model and spokesperson. Here’s a peek at her life and how she looks now.

We all have various appearances, which is what makes us unique and intriguing. Some people grow up tall, some short, some gain weight readily, and some don’t gain a pound despite poor eating habits. We all have various hair colours – or none at all. Everyone has characteristics that set them apart.

Every year, newborns are born with unique syndromes, diagnoses, or facial features. It can certainly make life more difficult, but in truth, folks with these distinct facial features are the strongest and most daring of us all.

Victoria Wright is one person to whom this certainly applies. She was born with cherubism, a rare genetic disorder characterised by varying degrees of aberrant bone outgrowth on the lower face. As a result, she was tormented in school and given different derogatory nicknames, and she still receives unpleasant comments as an adult.

Victoria, on the other hand, would never allow the bullies triumph. Instead, she became a role model for people all around the world, and she decided to use humour to show the world what it’s like to live with a facial impairment. Her inspiring tale is worth sharing, and we would appreciate it if you would forward this post to your friends and family!

Victoria, on the other hand, would never allow the bullies triumph. Instead, she became a role model for people all around the world, and she decided to use humour to show the world what it’s like to live with a facial impairment. Her inspiring tale is worth sharing, and we would appreciate it if you would forward this post to your friends and family!

When Victoria Wright was born, she was just like any other baby. Her parents were overjoyed for their beloved daughter, and everything seemed to be going swimmingly. But everything changed when she was four years old.

“My mum was brushing my teeth, and she noticed they weren’t in the right place,” Victoria Wright told NHS.

Cherubism, an uncommon hereditary disorder characterised by varying degrees of aberrant bone outgrowth of the lower half of the face, had manifested itself. It was named after the angelic figures shown as chubby-cheeked in Renaissance art.

Victoria and her family went to medical professionals, who indeed confirmed that cherubism had been detected. They told the Wrights that Victoria’s condition would regress after puberty. However, as we know today, that didn’t happen.

Instead, Victoria Wright’s jaw grew larger, and it didn’t take long before it began affecting her eyes. The pressure on her eyes became more and more severe. It got to a point where something needed to be done.

She underwent surgery to remove the pressure, which saved her sight. However, she still suffers from headaches as a result of her compromised vision.

“Cherubism is a painful condition.” I do experience pain. My head is heaving. “Doctors say it’s the weight of a bowling ball,” Wright said.

“I’ve been offered surgery to reduce the size of my jaw, but I don’t believe it would improve my appearance.” “I’m used to how I look.”

When Victoria Wright entered school, her life became difficult. In an article for The Guardian, she revealed how she was bullied, threatened with violence, intimidated, and verbally abused on the street and on public transit.

Victoria was given nicknames at school, including Fat Chin, Buzz Lightyear (the astronaut character from Toy Story), and Desperate Dan (a wild west figure from the Scottish comic magazine The Dandy).

“A girl in class used to draw pictures of me and share them around,” Victoria explained.

People stared at Victoria everywhere she went, whether she was at school, on the bus, or going down the street. She never got used to the looks, but she realised it was only natural.

“I make an effort not to take it personally. “Even I am staring,” Wright added.

“I used to get angry as a teenager, but it doesn’t help you or the person staring.” It simply feeds the idea that persons with disfigurements are angry, tragic, or frightening. It can be disconcerting if I find myself being aggressively glared at. But it doesn’t bother me.”

“If someone is staring out of curiosity, I just smile and nod to show them I’m a human being with nothing to be afraid of,” she explained. Most of the time, people return your smile. That makes me happy because I know I’ve built a small connection with them.”

Victoria Wright’s life altered when she reached the age of adolescence. She discovered Changing Faces, which has now grown to become the UK’s premier charity for people who have a scar, mark, or ailment on their face or body. Their website states that they “provide life-changing mental health, wellbeing, and skin camouflage services” and that they “work to transform understanding and acceptance of visible difference, as well as campaign to reduce prejudice and discrimination.”

Victoria found a lot of help through Changing Faces. Aside from her family, friends, and teachers at school, the foundation was critical in helping her realise that, despite her facial impairment, she was as valuable as everyone else.

“When I met them as a teenager, I thought, ‘Wow, you can have a career and be happy and confident with a disfigurement,’” she told NHS.

“It’s natural to feel isolated at times, especially if you have a rare condition.” It’s challenging when you don’t see anyone else on the street who looks like you. It is critical to seek peer support. For every person who looks, there are a hundred who do not and will appreciate and respect you for who you are.”

Wright gained a fresh perspective on her life after watching Changing Faces. She began to recognise the benefits and even developed a funny stance on her appearance. She told 60 Minutes Australia that she “adores” Toy Story’s Buzz Lightyear and considers him to be her brother.

Many individuals have questioned Victoria’s decision to forego plastic surgery in order to ‘do something’ about her features. Because of this, she has been inaccurately represented in the media as being anti-cosmetic surgery.

In actuality, Victoria Wright is not opposed to cosmetic surgery. The most essential thing is to be happy with how one looks in their own eyes – and she is.

“I’m not opposed to people with disfigurements having surgery, but I’m happy with the way I look.” “Why should I have the surgery for the sake of others?” Victoria Wright inquired.

“Most days, I’m pleased with my face. After all, I’m a woman, and no woman is totally satisfied with her appearance. But I’m not going to change myself just to please other people.”

“I don’t want to hide at home, afraid to go out and afraid of other people,” she added. If they don’t like the way I appear, that’s their problem, not mine.”

Victoria Wright gained a broader following in 2016 when she appeared in the BAFTA-nominated comedy-drama mockumentary Cast Offs. It followed six disabled individuals.

There was one blind man, one paraplegic man, and Victoria, who has cherubism. According to The Guardian, each role was performed by a disabled actor with the same disability, and one even expressed dissatisfaction with the amount of non-disabled actors portraying disabled people:

“There will almost certainly be a flood of comments from both disabled and non-disabled people regarding Cast Offs.” Some disabled individuals will find the portrayal of disabled persons as adults who curse, drink, and have sex amusing and realistic. A refreshing change from either concealing disability with child gloves or not covering it at all. Others might find it disrespectful’, Liz Sayce, CEO of the Royal Association of Disability Rights, told the newspaper.

For Victoria, doing the performance was nothing short of incredible, and in a Q&A she led with directors Miranda Bowen and Amanda Boyle, they recounted a short but telling narrative about her, which she opted to turn amusing once again.

“I remember you had to invent a secret in your casting, Victoria.” You said that you got plastic surgery to make yourself look humorous. I recall the expression on the face of the person you were acting with. “It was a brave, bold, and funny moment – everything we wanted,” Boyle added.

“I often forgot that neither of you [Victoria and co-star Peter Michell] had ever acted before,” Miranda continued. You both performed with wonderful professionalism and proficiency, and it was a pleasure to work with such a brilliant cast.”

Victoria Wright’s life developed with delight; she is now a loving mother and an active disability rights activist.

She has also been the UK spokesperson for Jeans for Genes, an annual fundraising event for the genetic disorder community.

“I’ve met people throughout my life who assume that because of how I look, I must live a depressing, isolated life, but I have a good life.” “I’m a charity activist and public relations professional with a young daughter who makes me laugh every day,” she explained.

Victoria Wright inspires so many people, disabled or not. She teaches us to be humble and proud of ourselves, as we should all be.